| Search | | People | | Calendar | | Internal Resources | | Home |

Crustal Deformation and Fault Mechanics |

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Migration of Tremor and Slip in CascadiaThe Cascadia subduction zone, where the

Juan de Fuca

tectonic plate converges with the North American tectonic

plate, hosts

magnitude 8-9+ megathrust earthquakes with an inter-event

time estimated to be

300-500 years.

The last such

earthquake occurred on January 26, 1700 and had an

estimated magnitude of

9. In

between these earthquakes

the subduction zone is not quiescent, but rather hosts

repeating slow slip

events and tectonic tremor, together referred to as

Episodic Tremor and Slip (ETS). ETS occurs on the deep extent of the

plate interface, deeper than the main earthquake region,

and repeats with intervals

in the range of 1-2 years depending on location. ETS is composed of slow slip on the

plate interface, at the

rate of about 2 mm/day, and small low-frequency seismic

signals called

tremor. The

combined moment of the

recorded tremor from seismic stations is much smaller than

the total moment of

slip recorded by GPS stations, implying that much of the

plate interface is

slipping aseismically.

This slow

aseismic slip is recorded on the surface as ~1cm

displacements on a network of

GPS stations. Studying ETS contributes to our general

understanding of

subduction since it has been detected in multiple places

around the world. In

particular, it is debated whether a

large megathrust would rupture into the ETS region, or

stop updip. Further

understanding of the physics of

ETS is needed to answer this question.

If the megathrust does rupture into this region,

the shaking in cities

near the coast such as Seattle and Portland will be

greater. In

addition, since ETS occurs

frequently, it provides an opportunity to monitor for

changes in the subduction

zone. It is

possible that ETS

monitoring may give us a recognizable precursor to any

large earthquake, but we

don’t yet understand ETS well enough to know. Noel Bartlow has been working on

contributing to the

understanding of ETS by studying how slip and tremor

migrate during an ETS

event. Although it is established that ETS is composed

aseismic slip and

tremor, which is in turn composed of individual small

low-frequency

earthquakes, the relationship between these two components

is not well

understood. Many

researchers have proposed

a model of a freely slipping interface with individual

“stuck” patches

representing tremor sources. These

patches are loaded by the slip until they “pop” giving off

seismic waves (see

Figure 1).

Figure

1. Schematic

diagrams of two possible

relationships between tremor and slow slip.

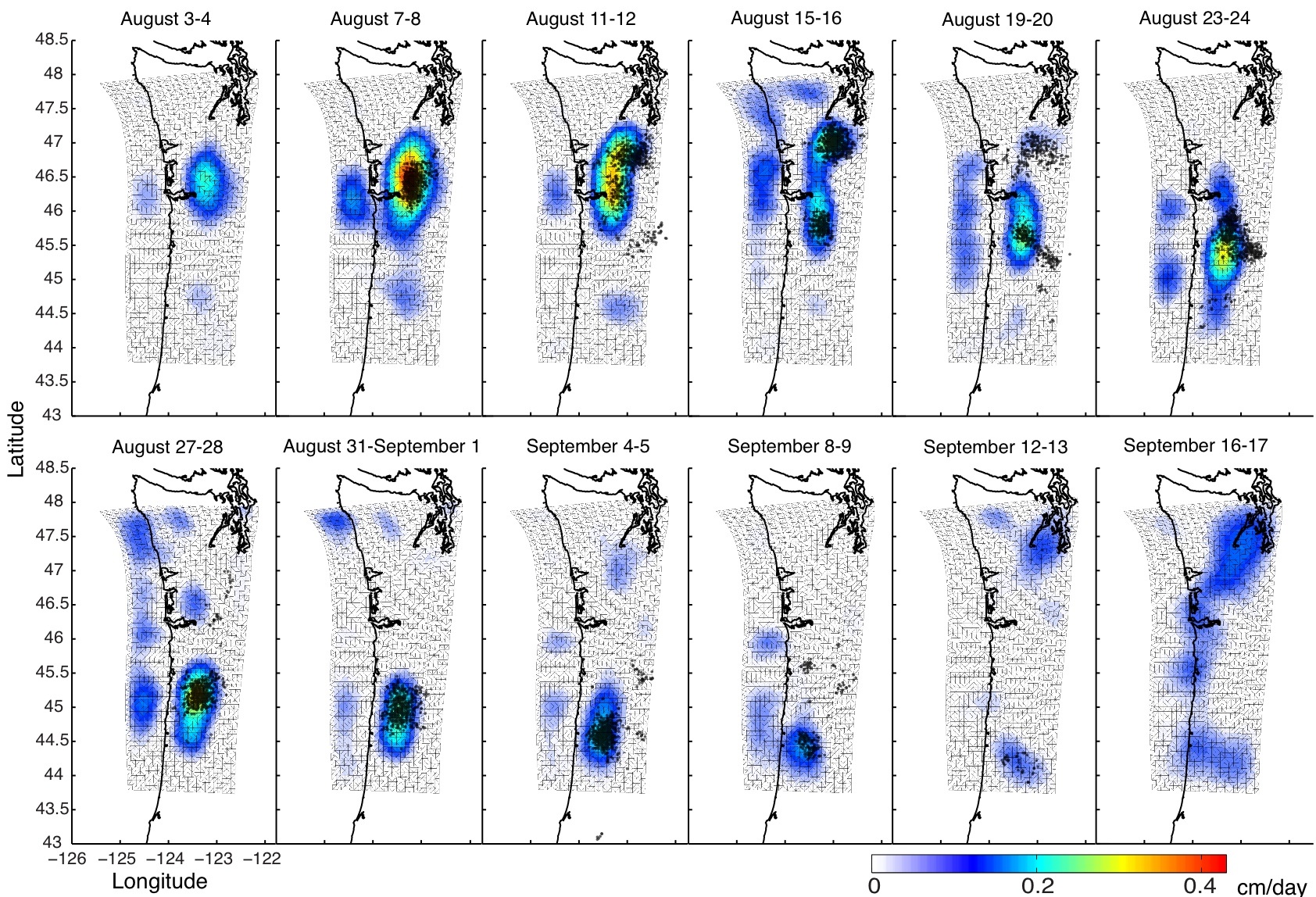

Figure

2.

Slip

rate on the plate

interface, averaged over two day intervals. Tremor

epicenters are plotted in

black for the same two-day intervals. The plate

interface mesh is shown between

10 and 60 km depth. Note that not all of the modeled

days are shown.

Figure 3. Left: Observed and predicted

cumulative GPS displacements during the 2009 ETS

event. Data and 1σ error ellipses shown in blue; model fit

shown in red. Labeled stations refer to time series fits shown

to the right. Right: Time series fits to GPS data

for selected stations.

|

| Last modified

Please contact the webmaster with suggestions or comments. |

|