|

|

|

Geodetic Strain used to improve earthquake forecasts in the

San Francisco Bay Region

Since H.F. Reid’s classic study of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake,

we have known that elastic strain accumulates slowly over centuries but

is released suddenly in great earthquakes. In Reid’s day crustal

strain was measured by repeated triangulation surveys, starting in the

1960’s with laser distance measuring devices, and in the last few

decades with continuous GPS networks. Geodetic strain plays a

central role in forecasting future seismic hazards: the higher

the rate of strain accumulation, either the more frequent or the larger

the earthquakes must ultimately be to relieve that strain. One of

our most important goals is to quantify these relations.

To accomplish this we require the most accurate measurements possible,

mechanically consistent physical models of the strain accumulation

process, and inversion methodologies to relate the data to the unknown

model parameters. With former student Kaj Johnson (Univ. Indiana)

we are applying these ideas to the San Francisco Bay area where several

major faults present significant hazards. Our goals are to

better constrain estimates of the long-term slip rates on these faults

and the average recurrence times of damaging earthquakes. We are

investigating how geodetic strain measurements can reduce uncertainties

in fault slip-rates and recurrence times inferred from paleoseismic

investigations.

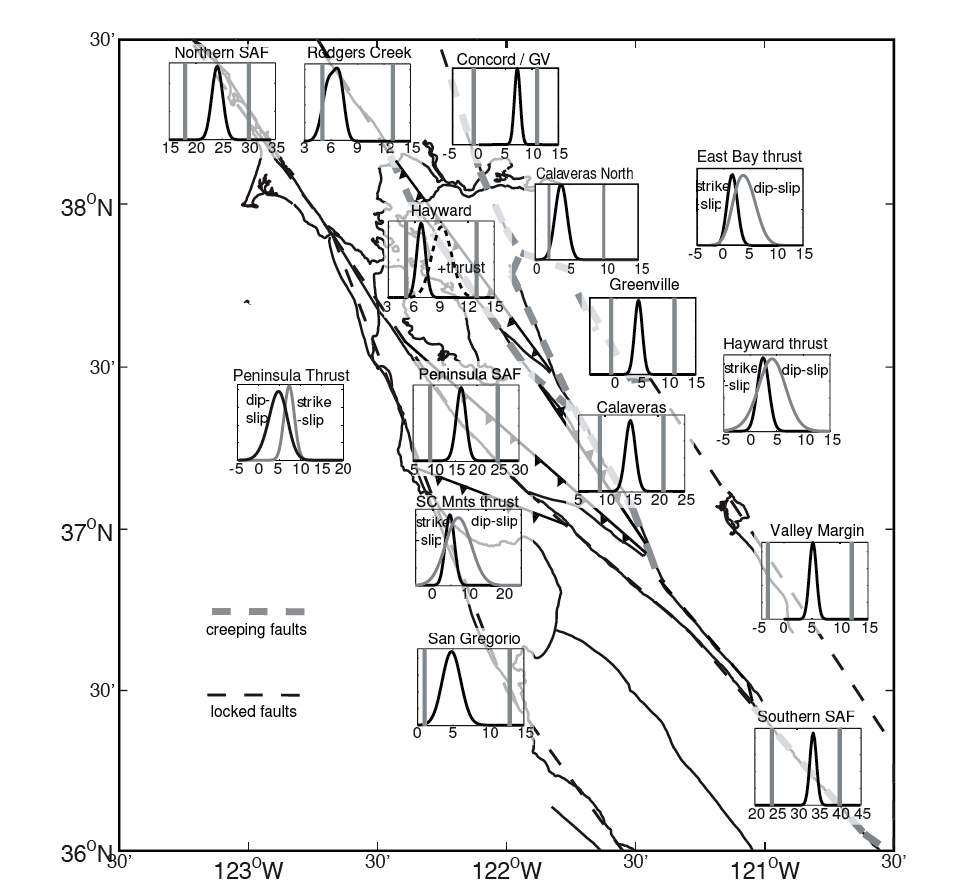

Figure 1: Average GPS velocities in the San

Francisco Bay region shown relative to stable North America. Also

shown are major creeping and locked faults.

Kaj has extended earlier two-dimensional models of faults in an elastic

layer overlying a viscoelastic lower crust and upper mantle to three

dimensions. This approach accounts for the long-term motion of

crustal blocks, but better accounts for geometric complexities where,

for example, thrust faults must accommodate motion oblique to the major

strike-slip faults. The deformation is rigorously coupled to the

visco-elastic substrate and we account analytically for an infinite

sequence of past repeating earthquakes.

The estimation strategy is based on a Bayesian analysis, where we take

the paleoseismic estimates of fault slip-rate and recurrence time as a

priori estimates (assumed to have uniform distribution between broad

lower and upper bounds). We then analyze the geodetic data and

compute posterior probability distributions on parameters of interest,

such as slip-rate and recurrence time.

Preliminary results demonstrate that the geodetic data provide strong

constraints on slip-rate as expected. For example the San Andreas

slips at rates near 33 mm/yr south of the Bay Area, but drops to below

15 mm/yr on the San Francisco Peninsula as slip is transferred to the

Hayward and Calaveras faults. The uncertainty in the recurrence

times of large earthquakes is only slightly reduced by adding the

geodetic observations: to 180-300 years on the San Andreas, vs 270-400

years on the Rogers Creek Fault. Further work will be required to

improve the mechanical forward models and to understand whether the

bounds on the recurrence times can be narrowed further.

Figure 2. Posterior probability density functions

for slip-rates on major fault segments. Prior bounds are shown by

gray bars.

Figure 3. Recurrence times for large earthquakes on

the San Andreas Fault Peninsula (upper left), north of the Bay (upper

right), and Rogers Creek fault (lower left). The most recent

earthquake on the San Andreas is 1906. Estimates of the most

recent large quake on the Rogers Creek Fault are shown in the lower

right. Grey bars represent prior bounds. Dark bars represent 95%

confidence intervals on the posterior distribution.

|